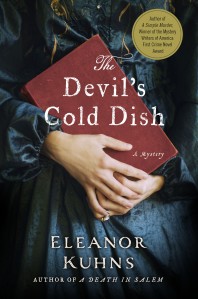

With the release of my new book, The Devil’s Cold Dish, just over a week away, I decided to reprise some of my research and the reasons I wrote this book.

Witches and Witchcraft – Not just Salem

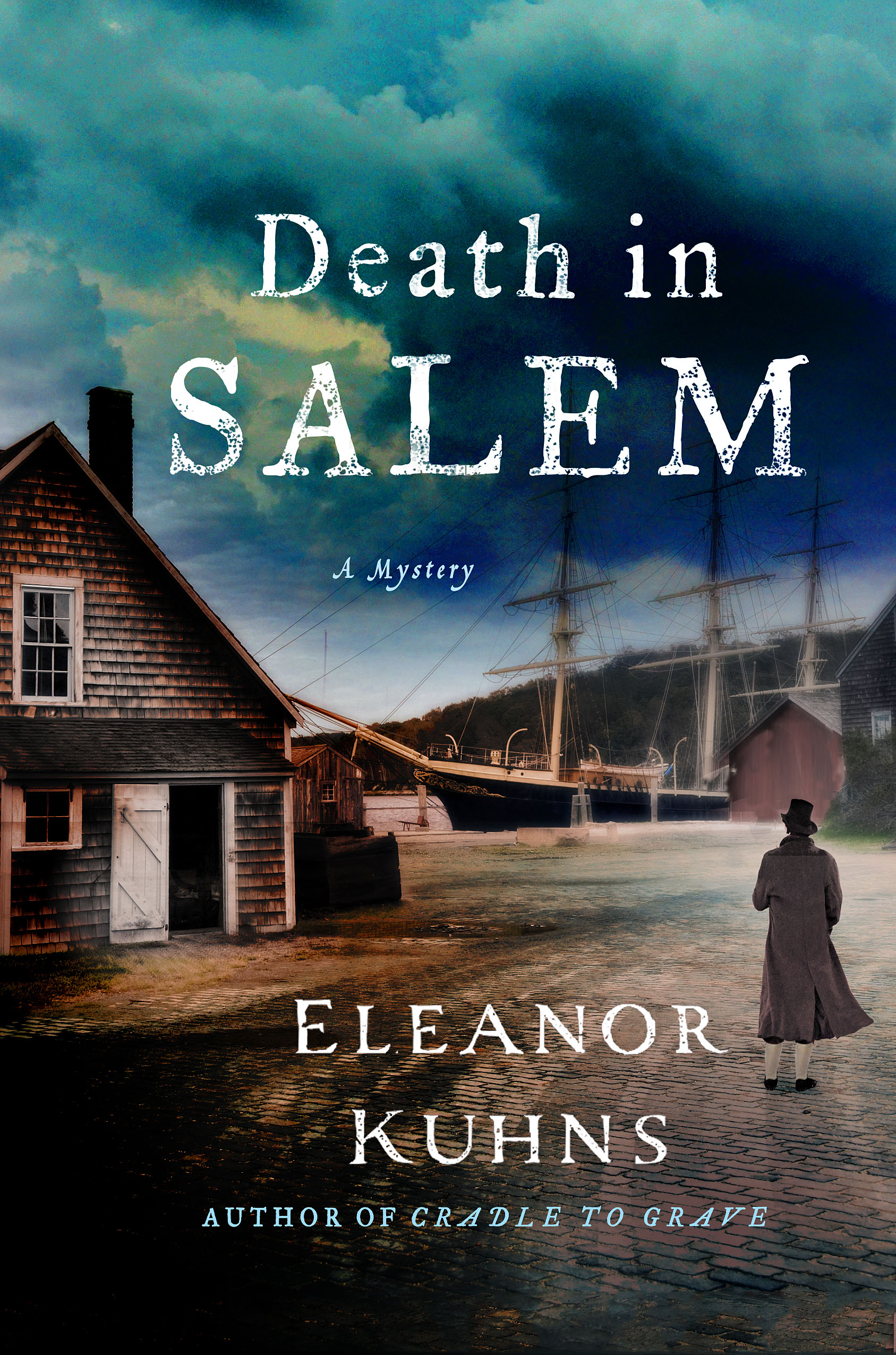

While I was researching Death in Salem, I visited this city several times. Since Will Rees, my amateur detective (and traveling weaver) visits Salem in the mid 1790’s. a full one hundred years after the trials, I did not write about them. I alluded to them of course but by 1796 Salem is a wealthy and cosmopolitan city, the wealthiest in the new United States and the sixth largest.

But I couldn’t get the witch trials out of my head. Why did it happen? What happened to the people afterwards, especially to the people who saw their loved ones accused and, in some cases, hanged? That question formed the beginning of The Devil’s Cold Dish.

The facts of Salem’s witch trials are these. In 1692, a group of girls including the daughters of the village minister Samuel Parrish claimed that they were being tormented by witches – and the girls accused some of the women in Danvers (this did not happen in Salem but within a small village just outside). Before the fury ended,150 people were imprisoned and 19 people – and two dogs- were hanged.

Because the people executed as witches were not allowed to be buried in sacred ground, the cemetery in Salem has monuments bearing witness to the names. No one is sure where these people are buried. It is thought the families cut down many of the accused after they were hung and buried them in secret.

One man, Giles Corey, was pressed to death. He cursed all future Sheriffs of Salem to die of some chest (respiratory) illness. Apparently most have, but in an era without antibiotics (forget about good hygiene or healthy food) I don’t think that is surprising.

What happened? Reasons given for the explosion of belief and hangings in Salem are many.

This event occurred in Massachusetts after several centuries of the trials and burnings in Europe. Probably everyone is familiar with the Biblical injunction about not suffering a witch to live. In 1200 Pope Gregory IX authorized the killing of witches. In 1498 Pope Innocent VIII issued a declaration confirming the existence of witches and inquisition began. Thousands, mainly women, were burned at the stake during the 1500s and 1600s. (Accused witches in this country were never burned. They were hanged instead.)

This was a superstitious age and belief in magic was widespread. Girls used spells to try and see the faces of future husbands and superstitions regarding illness, birth, and harvest were rife. Harelips were caused when the mother saw a rabbit, birth marks because the mother ate strawberries, for example. One of my favorites: to protect a mother and child during birth an ear of corn was placed on the mother’s belly. But I can’t believe EVERYONE believed in the supernatural. In fact, one of the essayists of the time, Robert Calef, suggested that the trials had been engineered by Cotton Mather for personal gain. (I doubt that. Evidently fighting out different opinions in print is not a new phenomenon). And anyway, other motivations for accusing someone of witchcraft have been documented. Sometimes it was for gain: the old biddy hasn’t died and I want her little farm, for example. (No surprise there, right?) Sometimes it was to settle scores. Apparently at least part of the reason behind the accusations directed at the Nurse family had at the bottom resentment and the desire for payback.

Tituba, a slave owned by Samuel Parrish, and her stories she told the girls played a part. Variously described as an Indian or a black slave, her testimony apparently drove much of the content of the stories and was a direct cause of the eventual hangings of women described as her confederates. (Ironically, Tituba was set free.) A shadowy character, she has been also described as practicing voodoo. Her testimony. at least to me, reads more like the Christian belief in demons and the devil. Once she was released, however, she, like the girls whose fits started the terror, faded into obscurity.

Then there are the girls themselves. To modern eyes, the easy belief in the veracity of a group of girls is incredible. Samuel Parrish believed in the truth of the accusations until the end of his life. I suspect there is another explanation. Women, and young girls especially, at this time were supposed to be quiet, meek and submissive. The claims made by these girls and the charges against others in the village put them on center stage. I do not wonder that they kept ratcheting up their stories; anything to keep that attention.

Then there is the possibility of ergot poisoning. Ergot is a fungus that grows on rye during wet and cool summers. It releases a toxin similar to LSD. So it is possible that people were genuinely suffering hallucinations.

The hysteria ended in 1693. After 1700 reparations began to be paid to the surviving victims and families of the executed. But belief in witches and the trials did not end. In the new United States a trial and a judicial solution to perceived witch craft became unlikely (and I imagine that the uncritical acceptance of spectral evidence by Samuel Parris in Salem had a lot to do with increasing skepticism) but accusation and hanging by mobs could still happen.

In Europe women were still attacked and in some cases executed for witchcraft: in Denmark – (1800), in Poland( 1836) and even in Britain (1863). Violence continued in France through the 1830’s. Accusations continued in the United States as well. In the 1830s a prosecution was begun against a man (yes) in Tennessee.

Even as recently as 1997 two Russian farmers killed a woman and injured members of her family for the use of folk magic against them.